DUCKWEED DAIRY

2025

Duckweed Dairy is a research project investigating the potential of duckweed as a plant-based protein source in the Dutch context. The work examines what is takes to grow, process and prepare the plant as food, focusing on low-tech cultivation and the development of a plant-based milk.

The project centred on practical experimentation: cultivating, drying and processing duckweed; producing small batches of test milks; and

organising tasting sessions that opened discussions about acceptance, sustainability and the cultural framing of plant-based milk. The work took place across the EnergieKas ponds and greenhouse, through expert interviews, in a small lab and kitchen setup, and during public tastings.

Duckweed Dairy recognises food as a social and ecological network. By approaching duckweed as

a local protein source, the project addresses issues of food safety, resource use and cultural perceptions of taste, while examining how this often-overlooked aquatic plant might inform new narratives about future nutrition.

Energiekas provided essential support, including space, guidance and opportunities for collaborative exchange within their network of neighbours, gardeners, artists and researchers.

Early advice from Studio Makkink & Bey’s Waterschool helped shape the project’s initial direction.

Funding was provided through the Experiment Grant framework of the Stimuleringsfonds Creative Industries.

The project centred on practical experimentation: cultivating, drying and processing duckweed; producing small batches of test milks; and

organising tasting sessions that opened discussions about acceptance, sustainability and the cultural framing of plant-based milk. The work took place across the EnergieKas ponds and greenhouse, through expert interviews, in a small lab and kitchen setup, and during public tastings.

Duckweed Dairy recognises food as a social and ecological network. By approaching duckweed as

a local protein source, the project addresses issues of food safety, resource use and cultural perceptions of taste, while examining how this often-overlooked aquatic plant might inform new narratives about future nutrition.

Energiekas provided essential support, including space, guidance and opportunities for collaborative exchange within their network of neighbours, gardeners, artists and researchers.

Early advice from Studio Makkink & Bey’s Waterschool helped shape the project’s initial direction.

Funding was provided through the Experiment Grant framework of the Stimuleringsfonds Creative Industries.

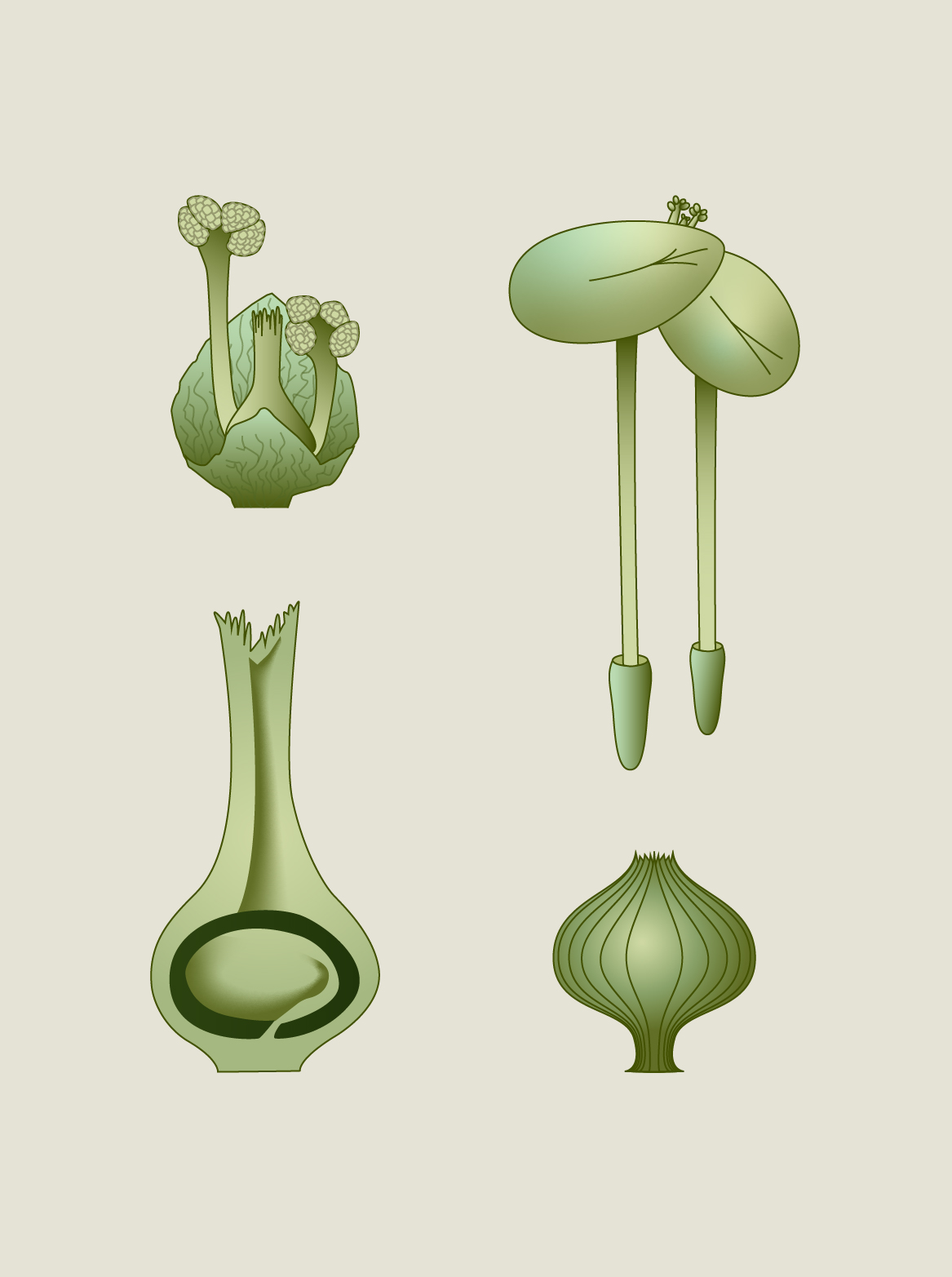

1. Duckweed

One of the fastest-growing plants in the world, duckweed has been a feature of Dutch waterways for centuries. Historically, it has appeared in farming manuals as a source of livestock feed and in botanical records as an indicator of water quality. Today, its high protein content, rapid biomass production and minimal land requirements are being studied, making it a relevant candidate for discussions about future food production and low-impact agriculture.

One of the fastest-growing plants in the world, duckweed has been a feature of Dutch waterways for centuries. Historically, it has appeared in farming manuals as a source of livestock feed and in botanical records as an indicator of water quality. Today, its high protein content, rapid biomass production and minimal land requirements are being studied, making it a relevant candidate for discussions about future food production and low-impact agriculture.

2. Protein Transition

The protein transition describes the shift from animal-based protein sources towards more sustainable, plant-based alternatives. This shift is a response to pressures on land use, emissions from dairy and livestock, and the need for protein to be produced locally within European food systems. Duckweed is relevant in this context because it grows without soil, recovers nutrients from water, and produces more protein per square metre than many terrestrial crops.

The protein transition describes the shift from animal-based protein sources towards more sustainable, plant-based alternatives. This shift is a response to pressures on land use, emissions from dairy and livestock, and the need for protein to be produced locally within European food systems. Duckweed is relevant in this context because it grows without soil, recovers nutrients from water, and produces more protein per square metre than many terrestrial crops.

3. Experiments

The experiments explored different ways of growing and preparing duckweed.

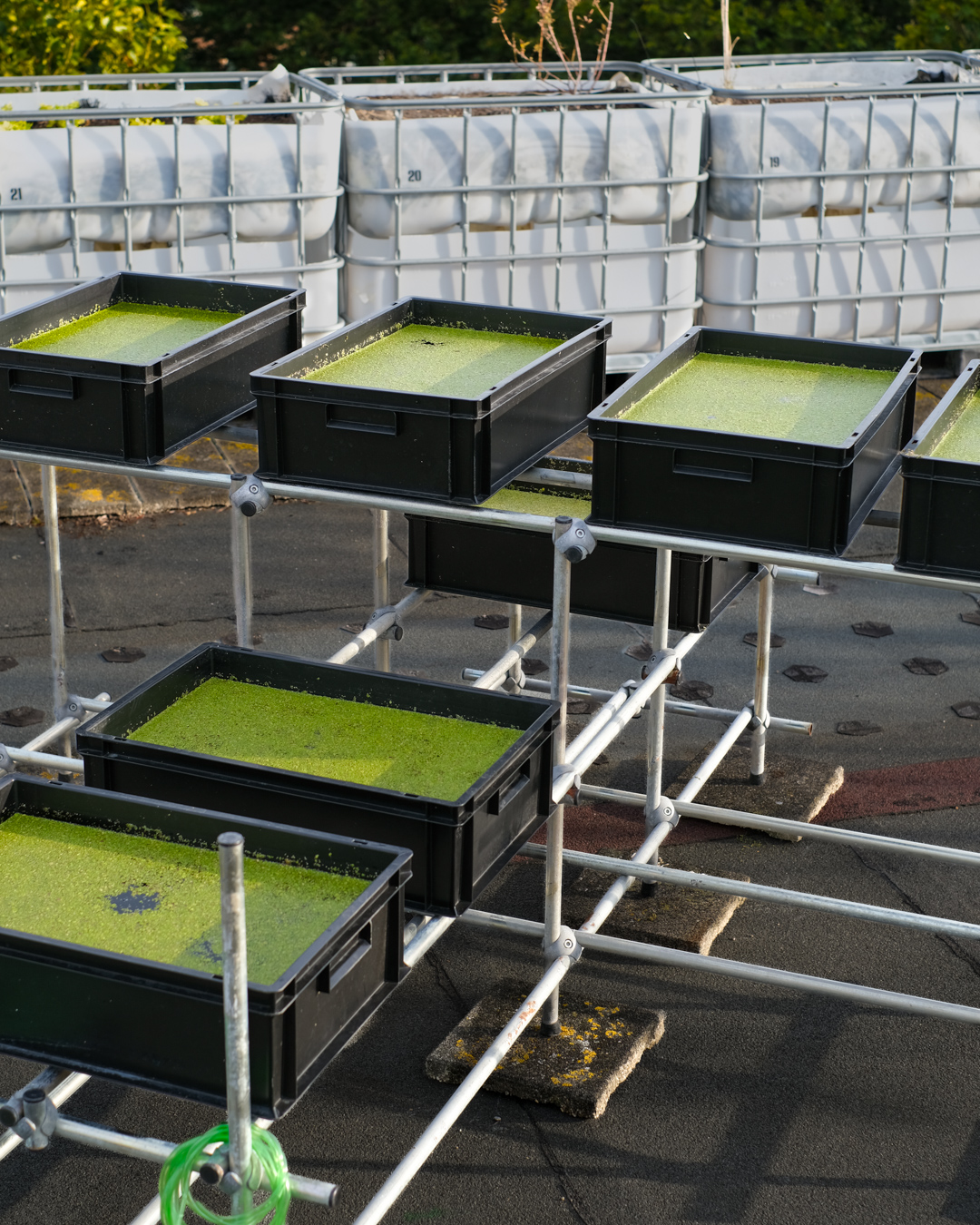

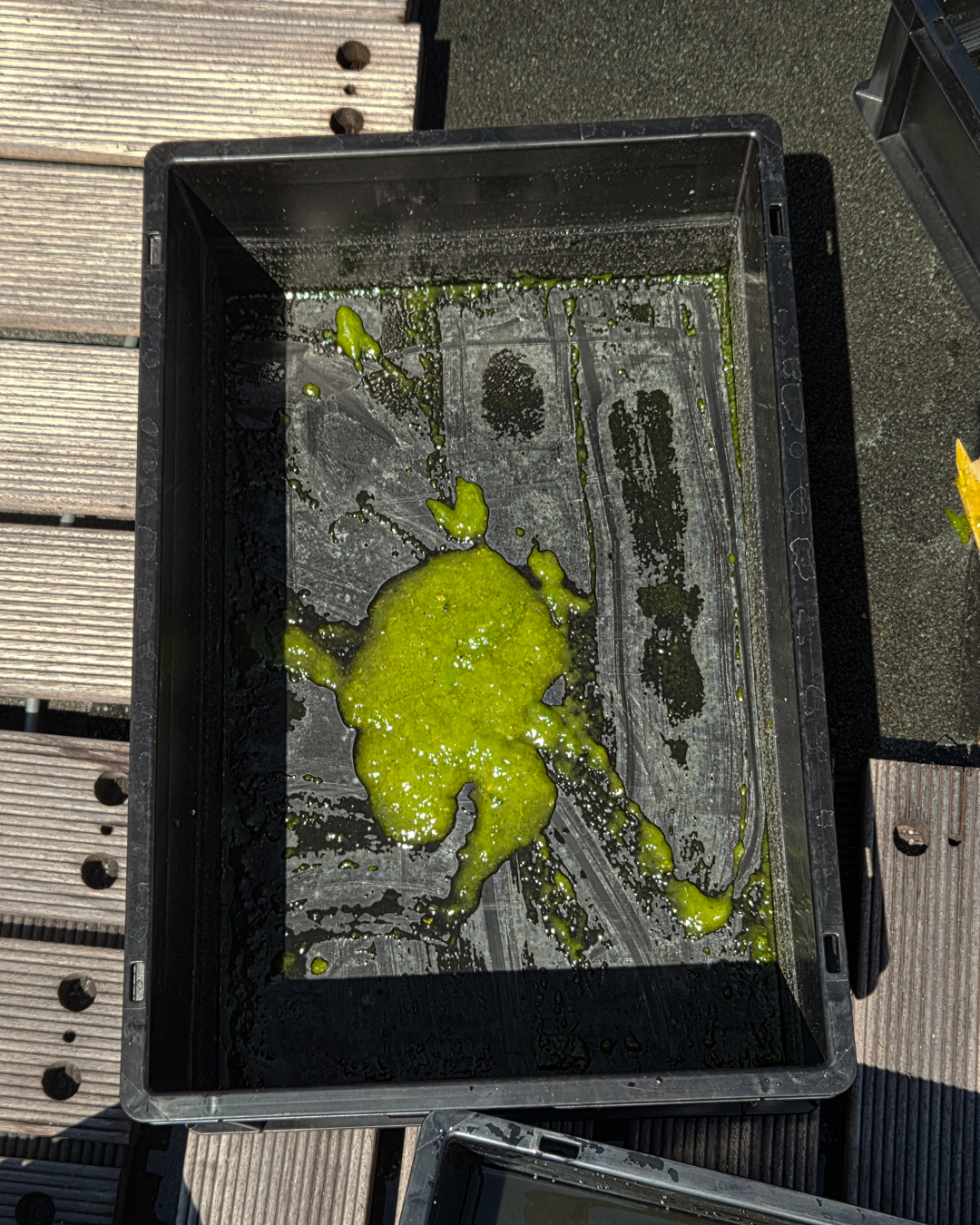

A small growing station with various tubs and containers was set up on the rooftop of EnergieKas. Duckweed was collected from several locations and additional plants were purchased from an aquarium shop in order to compare the behaviour of plants from different sources. The water was changed weekly and the condition of the plants was observed. Different nutrient levels were also tested to see which supported better growth.

Bruno Szenk built a simple rack for drying the duckweed, which could be spread out in a thin layer. Once dry, it was ground into a fine powder. Later in the process, the self-grown duckweed had to be excluded from tastings for safety reasons. Therefore, all edible tests used pre-milled, food-grade duckweed.

A series of kitchen experiments was then carried out with this powder: it was cooked, steamed, baked and combined with different ingredients. The aim was to find a preparation that tasted pleasant and could be used as a plant-based milk substitute. These practical tests provided valuable insights into how duckweed behaves in everyday cooking and its potential as an ingredient.

The experiments explored different ways of growing and preparing duckweed.

A small growing station with various tubs and containers was set up on the rooftop of EnergieKas. Duckweed was collected from several locations and additional plants were purchased from an aquarium shop in order to compare the behaviour of plants from different sources. The water was changed weekly and the condition of the plants was observed. Different nutrient levels were also tested to see which supported better growth.

Bruno Szenk built a simple rack for drying the duckweed, which could be spread out in a thin layer. Once dry, it was ground into a fine powder. Later in the process, the self-grown duckweed had to be excluded from tastings for safety reasons. Therefore, all edible tests used pre-milled, food-grade duckweed.

A series of kitchen experiments was then carried out with this powder: it was cooked, steamed, baked and combined with different ingredients. The aim was to find a preparation that tasted pleasant and could be used as a plant-based milk substitute. These practical tests provided valuable insights into how duckweed behaves in everyday cooking and its potential as an ingredient.

4. Tasting

As part of EnergieKas’ programme for the Spotlight Festival and Hoogtij, guided groups were invited to taste three versions of duckweed milk. These included a plain version made with only duckweed powder and water, a version blended with hemp seeds and a version prepared with hazelnuts.

Visitors approached the tasting with varying levels of curiosity. Some were hesitant, taking only a small sip, while others were more adventurous, closely comparing the three versions. Many participants shared personal anecdotes about duckweed, ranging from childhood memories of ponds and gardening to professional experience in environmental or food-related fields. Others contributed professional insights from fields such as horticulture, ecology and nutrition.

The tastings provided an effective and simple way for people to engage with the project, linking flavour impressions with everyday knowledge and professional experience.

As part of EnergieKas’ programme for the Spotlight Festival and Hoogtij, guided groups were invited to taste three versions of duckweed milk. These included a plain version made with only duckweed powder and water, a version blended with hemp seeds and a version prepared with hazelnuts.

Visitors approached the tasting with varying levels of curiosity. Some were hesitant, taking only a small sip, while others were more adventurous, closely comparing the three versions. Many participants shared personal anecdotes about duckweed, ranging from childhood memories of ponds and gardening to professional experience in environmental or food-related fields. Others contributed professional insights from fields such as horticulture, ecology and nutrition.

The tastings provided an effective and simple way for people to engage with the project, linking flavour impressions with everyday knowledge and professional experience.